So you read online somewhere about some guy named Anderson or Lawrence and how they went to jail for civil contempt because they settled an offshore trust. Scared? Don’t be. Anderson and Lawrence (as well as every other case) are very fact-specific cases. Lets discuss both of them as well as some others.

In FTC v. Affordable Media, LLC , 179 F.3d 1228 (1999), Mr. and Mrs. Anderson accumulated close to $6.5 million through a Ponzi scheme, and transferred to cash to an offshore trust. The Andersons’ offshore trust was typical-an irrevocable trust that allowed the settlors (Andersons’) full access to the trust funds, unless the Andersons’ were being coerced to get funds by a court order or other authority. However, unlike most modern offshore trusts, the Andersons’ were co-trustees and trust protectors (they had the ability to remove the other trustee and appoint a new trustee in any jurisdiction). Upon request of the FTC, the Federal District Court issued an injunction ordering the Andersons’ to repatriate any assets held in their benefit offshore. Four days later, the Andersons’ sent a letter to the corporate trust protector to remove them as trustees and appoint a new trustee. After all of this, the assets truly were out of the Andersons’ control, and then the Court ordered them in contempt “for failing to repatriate the trust assets to the United States.”

On appeal, the Anderson’s argued that it was impossible for them to repatriate the offshore assets (note: the defense of “impossibility” is a valid defense), and so shouldn’t be held in contempt. The Appellate Court held that the Andersons’ did in fact have control, and so they originally could have repatriated the offshore assets. The Court provided three reasons that it believed the Andersons’ originally had control. First, the Andersons’ had been able to withdraw $1,000,000 from the trust to pay for taxes-they clearly exercised at least some control of the assets. Second, because the Andersons’ were trust protectors, they could have removed the Cook Islands co-trustee and appointed a U.S. trustee. Third, the “most telling evidence of Andersons’ control over the trust” is that after they knew they were in possible violation of contempt, they resigned as trust protectors. “This attempted resignation indicates that the Andersons’ knew that, as the protectors of the trust, they remained in control of the trust and could force the foreign trustee to repatriate the assets.”

So basically, because the Andersons’ had control of the trust assets, they were found liable of civil contempt for failing to repatriate the assets.

Three years later, the next landmark case came down from the Eleventh Circuit. In In Re Lawrence , 279 F.3d 1294 (2002), Mr. Lawrence settled an offshore trust in 1991. Legal trouble for Lawrence soon followed. Lawrence amended the trust instrument several times, each time trying to distance himself farther and farther from the trust assets. Finally, in 1999, two years after filing for bankruptcy, he made the trust irrevocable. The Bankruptcy Trustee didn’t buy it for second, and held that Lawrence exercised control over the assets, and therefore could have repatriated them. The Eleventh Circuit upheld the Bankruptcy Trustee’s decision.

From these two cases, we learn that the trust instrument must be irrevocable and the settlor cannot retain any control over the trust assets.

The next series of cases deal with settlor’s of offshore trusts that truly didn’t retain any control over the trust assets, so the various courts had to use state law to attempt to dismantle the offshore trusts.

In In Re Brooks, 217 B.R. 98 (1998), Mr. Brooks, using his wife as his alter-ego, settled two offshore trusts in the summer of 1990. In 1991, Mr. Brooks was forced into involuntary bankruptcy. This is still an early case, and if this case came before a court today, the court would probably just unwind the trust (and hold Brooks in civil contempt) for a fraudulent transfer, since he was trying to evade creditors by sending his money offshore. However, the Bankruptcy Trustee used state law, and state law did not recognize self-settled spendthrift trusts (which type of trust the offshore trusts were), and therefore held that Brooks was still the owner of the offshore trust funds. Although Brooks was still the owner of the offshore trust funds-at least according the the Bankruptcy Trustee-the assets were still offshore and out of the reach of any U.S. Bankruptcy Trustee.

This story probably didn’t end will for Brooks, not because of the offshore trust, but because he clearly was attempting to evade creditors. A similar story is found in In Re Portnoy , 201 B.R. 685 (1996). So basically, here, we learn: (1) that a court or bankruptcy trustee can apply state law (instead of the offshore law) to dismantle a offshore trust; and (2) that we shouldn’t send assets offshore to evade creditors-but this is nothing new. However, even if the court applied state law to declare the non-existence of an offshore trust, the court still should not hold the settlor in contempt (barring fraudulent transfer or control of the assets).

Now we move on the next series of cases, where the courts required the settlors to demonstrate that they are unable to repatriate assets and that the inability to repatriate was not self-created (i.e. fraudulent transfer).

S.E.C. v. Bilzerian, 112 F. Supp.2d 12 (2000) gives us some more definition. Bilzerian was convicted of securities fraud and conspiracy to defraud the United States. Prior to his conviction, he sent his ill-gotten assets to an offshore trust. The Court explains how to avoid civil contempt. Basically, if we created the bad situation ourselves through a fraudulent transfer and we can’t get the assets back, then too bad so sad-going to jail for civil contempt. If a settlor didn’t commit a fraudulent transfer by settling an offshore trust, then he must demonstrate a good-faith effort to comply with the court in repatriating the assets. In other words, if you (properly) settle an offshore trust and you weren’t trying to evade creditors, and creditors come later, you must make a good faith attempt to persuade the offshore trustee to repatriate the assets. Even if the trustee doesn’t send you trust assets to comply with a court order, then you are not liable for civil contempt. This is exactly what happened in U.S. v. Grant, 2008 WL 2894826. In 1983 and 1984, Mr. Grant settled offshore trusts-one for his benefit, and one for the benefit of his wife. Years later in 2003, Grant became liable for over $36,000,000 in unpaid taxes. Mr. Grant had passed away but the government went after Mrs. Grant, and the federal district court threatened her with contempt. With the help of legal representation, she attempted to repatriate assets by contacting the offshore trustees and financial institutions that held her assets, and also attempted to appoint new trustees. Though all these efforts failed to repatriate trust assets, the federal district court held “that Mrs. Grant has sufficiently established that she is not able to repatriate the offshore funds” and likewise found her not liable of civil contempt.

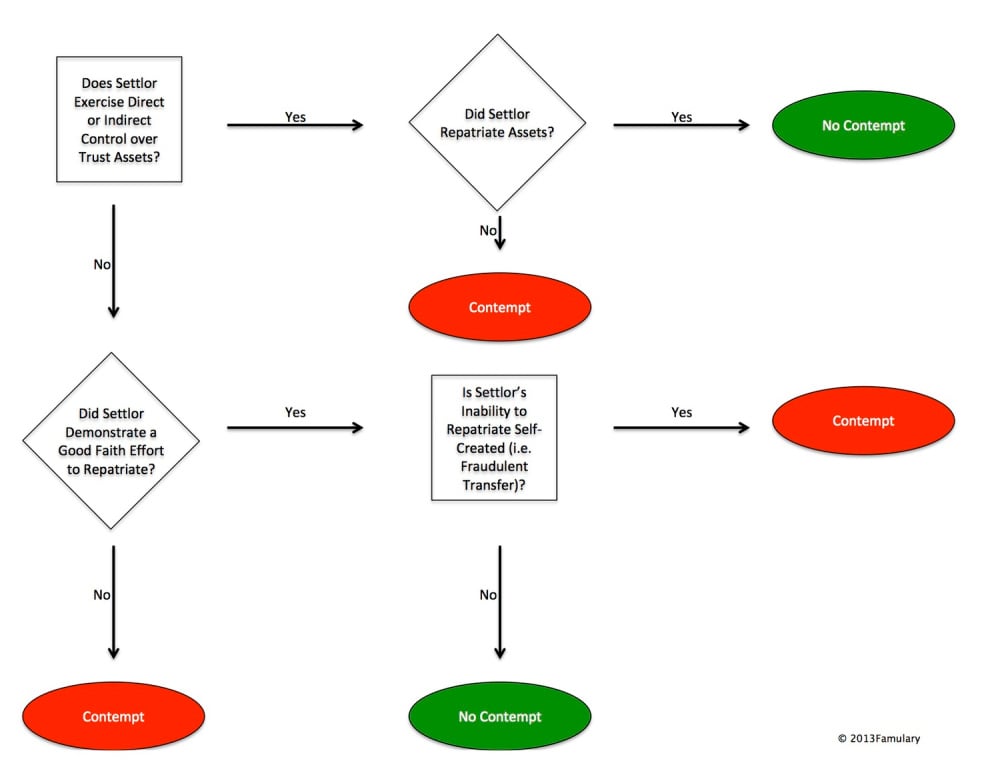

I have synthesized the rules in the above cases into a flowchart (below). Enjoy.